We make food value transparent

Are you a catering company or consulting company?

Strange though this may appear, we are both a caterer and a consulting company. Our vision early on was to be both:

- A real-life caterer serving food that embodies the values we espouse (transforming agriculture, food and health at the local level through technology and people engagement),

- A teaching and consulting enterprise helping others apply a similar model to their own business.

Simply put, we believe that credibility in consulting begins by applying your own concepts to the development of a successful business.

Two of us, Doctor Gary Epler and Francis Gouillart, started as consultants, in healthcare and ecosystem co-creation respectively. We then partnered with Chef Lorena Lorenzet who came from the world of food. We have since then built a community of experts around the three of us that brings us the necessary expertise in agriculture, food, health and technology, particularly sensors and the Internet of Things. We use Heritage Food Truck Catering as the laboratory through which we test our ideas for foods, but also for the intellectual property that surrounds that food.

What problem do you solve?

Differentiating the quality of food products is notoriously difficult. Consumers do not know how to distinguish between products, yet some products are better than others. The role of Heritage Food Systems Consulting is to “reveal” the value of your product to the people who consume or buy it. We are particularly interested in documenting the value of locally sourced, locally produced food (or in some cases, lack thereof).

What defines food value? Is there such a thing as “good food” or “quality food”?

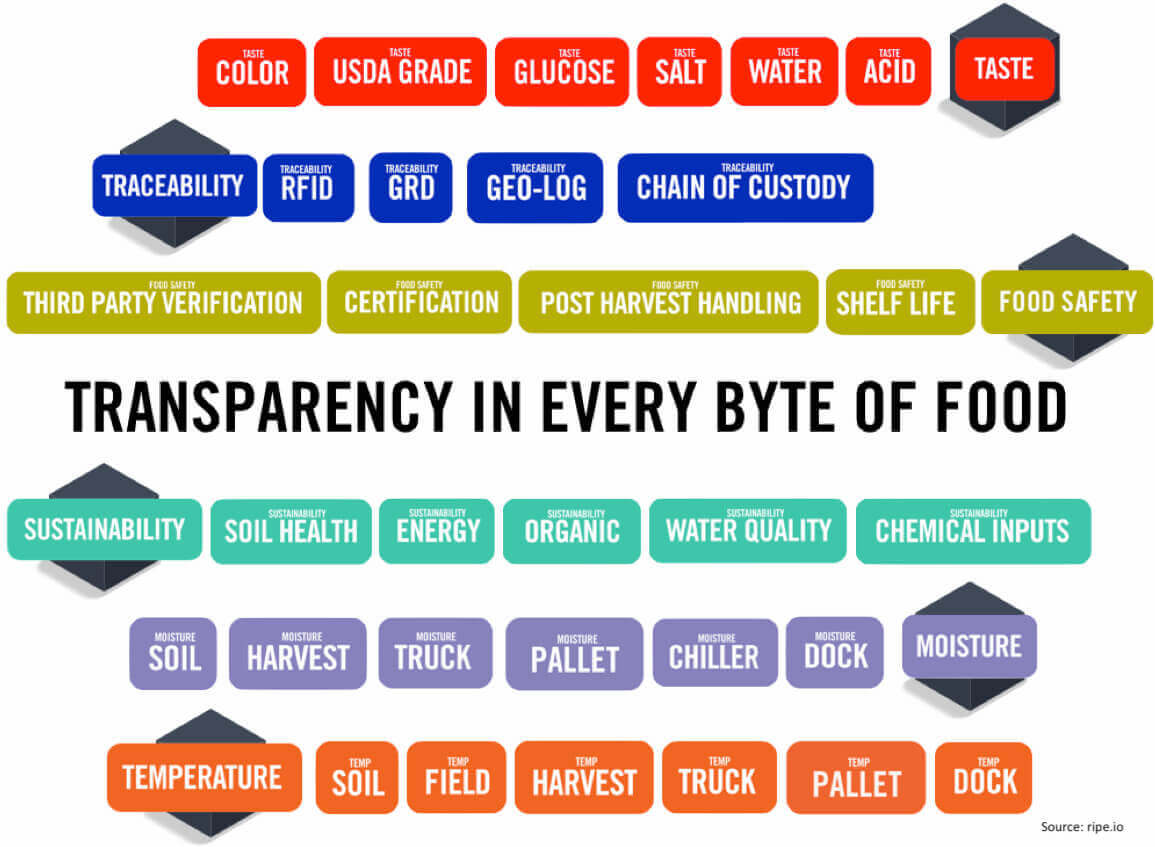

“Good food” or “quality food” are subjective concepts, which is why each food company should create its own definition. You make the claim, and we help you authenticate the claim by collecting data and analyzing it. View us as the data support for your marketing or merchandising department. Or your research department. Most food quality systems involve some combination of taste/flavor, nutritional content/health, appearance, cost, safety, sustainability and social justice, and we are equipped to collect data on all those dimensions.

How do you “reveal” the value of food products?

We instrument your supply chain with sensors that capture a lot of data about your product and add some manually collected, qualitative data. We send all that data into a data base, analyze it, and produce a value model that you can use for advertising or research purposes. We start by looking at the soil where the farm products are grown, the plant and the produce involved, then track it through storage, packing and transportation, and eventually across the retail, institutional kitchen or restaurant where it is sold and/or consumed. We also collect consumer preference and wellness data. This produces a digital record of data for your product and allows you to identify patterns of correlation across variables.

How does the process work in practice?

Heritage Food Systems Consulting is in the authentication business. You make a claim about your food, and we analyze for you whether your claim can be proven true or not. The formulation of the claim and the data are yours and yours only, and only you decide whether you want to put the result to use for commercial or research purposes. Our practice is rooted in hard science and we help you interpret the data into provable, marketable claims. We also help you prove or disprove research hypotheses.

What is unique about your consulting service?

We work for clients interested in understanding their food supply chain holistically through data that spans across agriculture, food and health. Many other organizations already work on optimizing each stage of the chain through the development of best practices in agronomy, food science and nutrition. What ultimately matters to consumers, though, is the product of all three, and this is where Heritage Food Systems Consulting comes in. We work with clients involved in agriculture, food and health who wish to make claims about what happens to their products and services upstream and downstream of their business. We also work with the investment and services industries that support agriculture, food and health.

How do I use this data in practice?

First, we can benchmark your product against competitors allowing you to brag about what you do better, backed by real data.

Second, you can open a creative dialog with your customers using the data we develop for you. Transparency is the backbone of consumer engagement.

Third, we help you discover how these variables relate to each other, e.g., what agronomic practices can increase nutrition content or taste, or working in reverse, how the recipe can change to maximize use of beneficial produce or land characteristics.

What skills do your consultants have?

Heritage Food Systems Consulting operates with a core staff of three people (Francis Gouillart, Dr. Gary Epler, Chef Lorena Lorenzet). We have assembled around us a community of experts who are both passionate about food systems (and particularly local food systems) and deeply knowledgeable about agriculture, food, health and technology.

More specifically, we have

- Agriculture experts who deal with measuring land- and farm-based variables and recording agronomic practices. This group is coordinated by Francis Gouillart.

- Food experts who work with you on distribution/logistics, food processing/food science and culinary issues. This community is facilitated by Chef Lorena Lorenzet.

- Healthcare experts who focus on nutrition content, the biology of human metabolism, and health outcomes. This group is orchestrated by Dr. Gary Epler.

- Technology experts who come in two flavors. Our Hardware Scientists work on selecting the best sensors and telecommunication solutions for our clients. Our Software Scientists worry about the choice of data base technologies (conventional, blockchain), application development and the development of analytical insights and algorithms, what is commonly referred to as Artificial Intelligence.

These four “technical” services are provided through a shared philosophy of organizational transformation we call “ecosystem co-creation”, a topic about which Francis Gouillart has written and published extensively.

An example of project: The Internet of Tomatoes project

What was the project about?

The Internet of Tomatoes project was commissioned by Analog Devices, Inc.. (ADI) in partnership with sweetgreen (restaurant), Costa Fruit and Produce (distribution) and Ward’s Berry Farm of Sharon, MA (farmer).

The idea behind the project was to collect data along the entire tomato Ag-Food value chain:

- from the farm (Ward’s Berry Farm)

- through the distribution stage (Costa Fruit and Produce)

- all the way to the consumption stage (sweetgreen restaurant downtown Boston),

through the use of sensor-based, Internet-of-Things technologies.

We engaged all actors in the value chain in a data-driven dialog aimed at transforming the overall quality of the finished tomato product and improving the efficiency of growing, distributing, processing, and retailing those tomatoes, which eventually led to the development of new practices, products or services in the tomato ecosystem that benefit all actors in the chain.

What’s new about this? Aren’t there lots of projects doing that already?

We wanted to create a longitudinal view of the whole tomato value chain from seed to mouth, resulting in an optimization of yield and agronomic practices at the growing stage, productivity at the distribution, processing and retailing stage, and cost, taste and health at the consumption stage.

While there are many sensor-based projects underway in specific stages of the Ag-Food chain (precision agriculture programs for corn and soybean, for example, or rating of produce sustainability by leading retailers such as Whole Foods), there has been very little farmers-to-consumers dialog rooted in the sharing of integrated value chain data. This has led to farmers and their suppliers being too narrowly focused on cost and productivity issues and potentially less sensitive to taste and environmental issues, and to consumers perhaps being unrealistic about the practical economics of tomato growing and distribution.

There has also been a lot of tension in the Ag-Food world about who should own such data and who should be allowed to monetize that data. Our Internet of Things project provided a neutral, transparent, data-driven view of productivity and quality along the tomato chain that led the various actors to different, mutually beneficial choices, thereby leading to a transformation of the entire value chain and fostering the development and sales of the enabling technologies and associated services.

Were you really just interested in tomatoes? Why did you pick tomatoes rather than say, grapes or rice?

Our ultimate goal was to pioneer a new ecosystem development model that extends beyond tomatoes to the entire global Ag-Food global ecosystem. While global scalability was – and still is –our ultimate goal, we believe the chances of success are highest by starting with a product-and geography-constrained “sliver” of the larger ecosystem, then gradually migrate to other produce and geographies.

We picked tomatoes because it is one of the largest produce market, because its value chain is not overwhelmed by a GMO quasi-religious battle that would cloud our data-driven approach (there is no GMO tomato as of today), because tomatoes are difficult to grow (numerous pest issues) and distribute (fragility, complex ripening cycle), because the current producing tomato areas in North America need to develop new paradigms of production (drought in California, sands of Florida, labor issues in Mexico) and because there are passionate lovers of tomatoes at the consumption stage who wish for tomato taste and flavor to be significantly improved.

What was the role of Analog Devices, Inc.? What was the role of Heritage Food Systems Consulting?

Analog Devices was the lead company and general contractor developing the technology stack used in the Internet of Tomatoes project, led by Rob O’Reilly, one of the company’s Senior Scientists. The technology included several of the company’s proprietary sensors and micro-controller, while leveraging multiple technical agreements or partnerships the company has with other companies. For example, ADI has an agreement with Consumer Physics of Israel whose molecular sensing device was integrated into the Internet of Tomatoes approach. ADI also provides the rapid-prototyping team needed to constantly adapt the technology to the need of tomato farmers and other value chain players in various parts of the world. The goal of the company was to become the leading Internet of Things infrastructure builder and data services provider for the Ag-Food vertical and the Internet of Tomatoes was its first foray into this vertical.

Heritage Food Systems Consulting acted as the project manager for the Internet of Tomatoes project on behalf of ADI. Its role was to utilize its knowledge of local Ag, Food and Health players, to assemble and manage for ADI the communities of farmers and other value chain providers who own and can use the data, to advocate for those data owners in monetizing their data with companies whose offerings can benefit from that data, and to offer those companies custom contract research services based on the Internet of Things infrastructure and basic data services made possible by the ADI technology.

To use a comparison with the more traditional division of labor in hardware, software or telecom services, ADI was the products company and Heritage Food Systems Consulting acted as the ecosystem integrator that supported the deployment of those products and provided customs research services.

How was the project funded?

ADI funded the Internet of Things project through the usual allocation of resources process inside a large public company.

What business methodology did you use to do the work?

We utilized the co-creation engagement process developed by Francis Gouillart, Founder and CEO of Heritage Food Systems Consulting, in two articles: Building the Co-Creative Enterprise, co-written with Venkat Ramaswamy, Harvard Business Review, October 2010 and Community-Powered Problem-Solving, co-written with Doug Billings, Harvard Business Review, April 2013.

What were the objectives of the project?

The objectives of the project were the following:

- Map out the Tech, Ag and Food components of the tomato ecosystem in greater Boston,

- Conduct the preliminary field work required to design the most promising working with Ward’s Berry Farm, Costa Fruit and Produce and sweetgreen,

- Help ADI identify the right technology stack (sensors, hardware, software, communication, analytics), as well as relevant agriculture and food data and processes that need to be considered to transform the tomato ecosystem in Boston,

- Initiate some experiments in various stages of the tomato value chain, i.e., put together a technology platform prototype, start collecting live data, set up a repository, initiate the development of some algorithms or applications.

What did the project achieve on the technology front?

The project was highly successful on both the technology and the market acceptance fronts. On the technology front, we can point to the following three major achievements:

- For the tomato in the field or in the greenhouse, we successfully developed a prototype using ADI’s platform that captures humidity, temperature and light data, transmits that data to a central cloud server that provides analytics-based prescriptions in real time to the farmer on items such as when and how much to water, when to open vents on tomato tunnels, or when to harvest. Our focus was on demonstrating technical feasibility (which we achieved successfully), not on collecting a large volume of data or developing algorithms (given that our sample was limited to one farm).

- For the finished tomato, we successfully built a tomato flavor/taste model that objectively measures intrinsic physical characteristics of the tomato, such as its sugars, acids, salt, water content, or lycopene content (anti-oxidant) and correlates those variables with the taste and flavor scores given by experts at the Boston Tomato Contest held at the Boston Public Market in the last three years. Through this event, we now have a data base of 100 different tomatoes from about 40 farmers across Massachusetts and have found some important correlations that enable farmers to alter their practices to improve their ranking at the Contest in the future.

- ADI has also successfully developed a prototype of an optical, noninvasive technology that can substitute for the invasive instruments used historically for the analysis of tomatoes (e.g., analyzing a solution through a pH meter, etc.). This near-infrared technology is allowing us to scan the same tomato at various stages of its development, from seed through its growth on the plant, its harvest, its distribution, retailing, kitchen processing and eventual consumption.

The ability of this new optical technology to create a longitudinal view of how the quality of a tomato forms over time is particularly crucial to our goal of allowing a rebalancing of the tomato value chain toward a better equilibrium between productivity, quality and sustainability, so we are happy to report that the technology developed potentially represents a major breakthrough for our project.

What did this project achieve on the market front?

Of course, technology is only helpful if it can lead to the development of a market willing to pay for the services arising from the technology. Given the complexity of the Ag-Food value chain and some of the battles currently waged over the ownership of the data, this is a particularly important area. Here are seven important things we learned from this project.

- Using the taste/flavor model described in the previous section, we found that local tomatoes from Ward’s Berry Farm are heads and shoulders superior to non-local tomatoes sourced from large retailers or local tomatoes grown in greenhouses. Ward’s Berry Farm tomatoes had significantly higher sugar content, higher salt content and more acidity. They also had a higher lycopene content (important anti-inflammatory properties) and had also logged significantly fewer miles than commercial tomatoes from supermarkets (sustainability).

- We were also able to show that the taste/flavor of tomatoes is a function of how much light they had received, how long they had been kept within a certain temperature bracket (not too cold, not too hot) and how little humidity they had been subjected to. While these three variables are generally known to drive yield in agricultural science, we proved that they also drive flavor. We were also able to show that the mandated practice by the Boston Board of Health to refrigerate tomatoes as soon as they leave the farm actually damages the flavor of tomatoes. Ward’s Berry Farm tomatoes continue to ripen off the vine for five or six days after harvest, so they should ideally be allowed to age for that period to reach their peak.

- Local farmers producing high-quality tomatoes proved very interested in advertising tomato data through our proprietary Internet of Things technology and are eager to use the data we provide out to improve their operations. Predictably, local farmers producing tomatoes of lower quality are less eager to make their data transparent. Suburban, retail-oriented farmers catering to sophisticated high-end customers are particularly interested in learning to optimize taste and flavor characteristics of their tomatoes and are envisioning pricing more aggressively for tomatoes with known beneficial characteristics. Wholesale-oriented farmers are focused on improving yields through better irrigation, temperature and light control, and on extracting a price premium for tomatoes known to possess particularly valuable properties.

- There is early evidence of the value of tomato data for both agriculture input and output companies. On the input side, seed, fertilizer and pesticide companies, are all eager to get access to actual yield data from their products in actual farms. This is equally true for local crop protection distributors and providers of agronomic services, for whom getting a continuous feed of live data would represent a more effective way to operate than the sporadic field interventions they do now.

- On the output side, distributors and retailers alike struggle with an average 8% waste due to uneven ripening of tomatoes that they would hope to reduce through a better prediction of the ripening/rotting trajectory of tomatoes they handle. Traders today buy tomatoes based on physical appearance and provenance labeling data but would love to develop pricing bids based on more objective characteristics of those tomatoes such as sugar, acid or water content. Retailers and chain restaurants would also like to be able to claim that their tomatoes have intrinsic characteristics that allows them to differentiate their offerings, as more and more of them utilize transparency of their suppliers’ practices as part of their branding.

- The project revealed the potentially unique role that consumers and chefs can play in demanding the development of a transparent, objective and comprehensive tomato scorecard encompassing all dimensions of tomato productivity, quality and sustainability. They play a key role in advocating for the value of technology in terms of public relations. In this project, we generated a high level of engagement through several public events in the Boston area (Boston Tomato Contest, “Let’s Talk about Food” forum, Ted X Cambridge exhibit), which allowed us to see how interested the general public is in a technology initiative that provides local farmers, chefs and consumers with the tools through which they can objectively assess the relative quality of tomatoes used for various culinary applications (“terroir tomatoes”).

- We were also able to generate great interest by creating a scientifically-designed, experimental tomato sauce through Heritage Food Truck Catering that produced a unique local heirloom tomato sauce through the use of our prototype technology and the data science it allows for a food producer